Could Light Be Used To Drive Enzymes for Efficient Ammonia Production?

Nanocrystal–Nitrogenase Biohybrids Harvest Light To Reduce N₂ Gas. Abundant High-Energy Electrons Are Essential.

Ammonia, a key part of nitrogen fertilizers, is central to sustaining global food production. However, its manufacture is also energy intensive: ammonia production requires 2% of global energy to meet global demand.

Fifty percent, or approximately 170 million metric tons, of the global supply of ammonia is produced by the Haber-Bosch process, a common industrial process. Biological nitrogen fixation produces the other 50% of the global ammonia supply. This process converts nitrogen in the air to ammonia using nitrogenase enzymes, a reaction that does not require high heat and pressure and is therefore much more energy efficient. Although the amount of ammonia it produces is equivalent to Haber-Bosch, biological nitrogen fixation is geographically distributed, making it challenging to use in supporting intensive, localized, industrial agriculture.

Molybdenum nitrogenase is one enzyme that can be used for biological nitrogen fixation. Three National Laboratory of the Rockies (NLR) researchers—joined by the University of Colorado Boulder, Utah State University, and the University of Oklahoma—examined the process of catalytic electron delivery into a molybdenum iron (MoFe) protein, an important component of N2 reduction, along with time-resolved detection of the reduction intermediates. The team developed a model to better understand the experimental conditions that support productive light-driven reduction of N2 to ammonia.

“Ammonia is a valuable commodity chemical and also a potential fuel, feedstock, and energy storage candidate and promising alternative marine fuel,” said NLR bioenergy and bioeconomy researcher David Mulder. “If we can understand how nitrogenase enzymes operate, we can guide the development of next-generation technologies and envision lower costs through strategies that lower the massive energy intensity of ammonia production.”

The work is detailed in a new Cell Reports Physical Science paper. Funding for this work was provided by the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science Basic Energy Sciences.

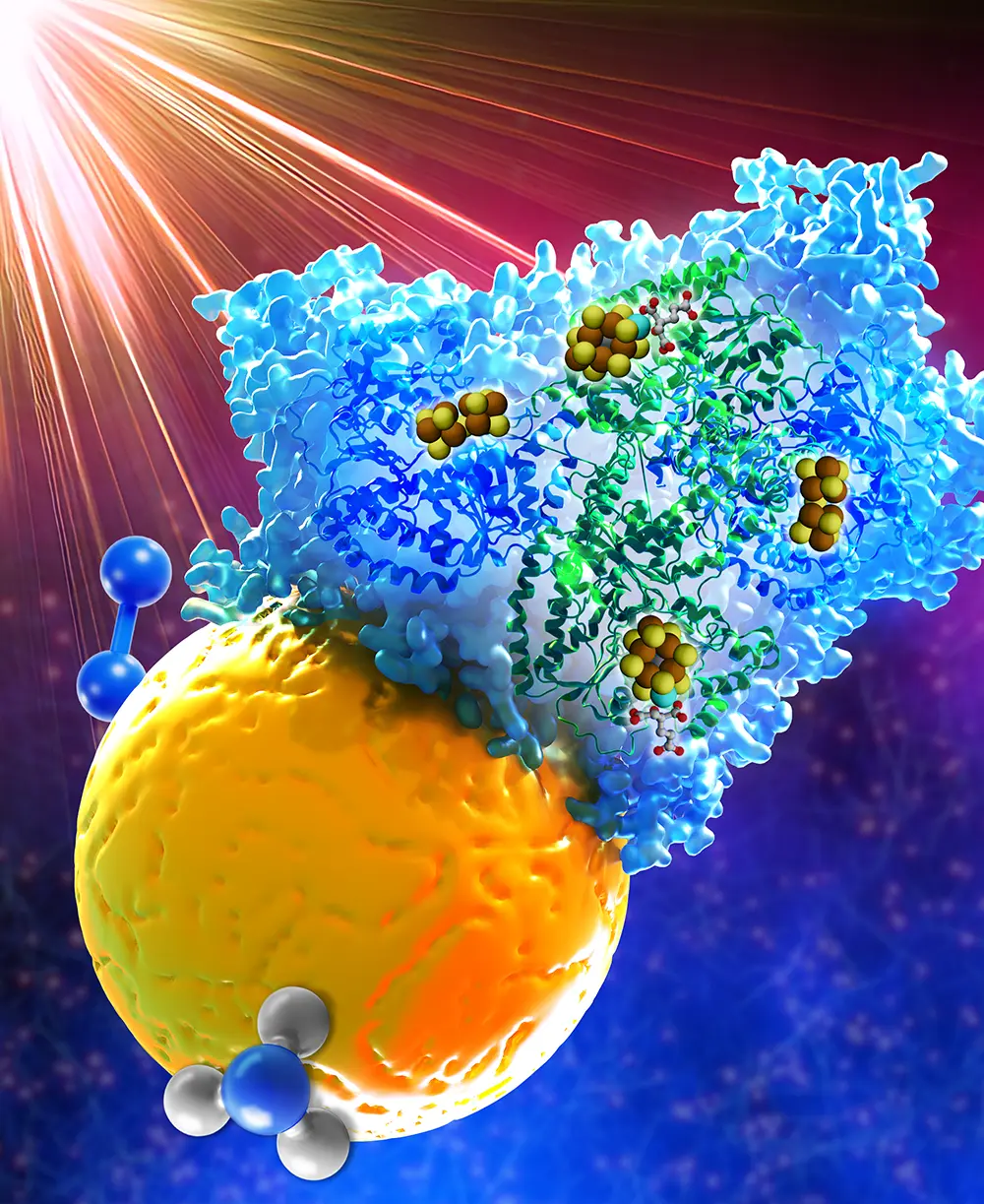

In previous work, the authors demonstrated that one part of the system—a specialized protein called the Fe protein that is required to deliver electrons to the MoFe protein (an essential step in the process to N2 reduction)—can be bypassed by using cadmium sulfide (CdS) nanocrystals that act as a catalytic mediator for the MoFe protein on the road to ammonia production. More specifically, the nanocrystals convert the energy of light into photoexcited electrons that the MoFe protein uses to catalyze the reaction. In the presence of CdS, the use of light, such as the sun or artificial LED illumination, can replace Fe protein—the source of ammonia production in nature—to provide the electrons needed to drive the reaction.

The researchers also demonstrated that they could trap and monitor the formation of reaction intermediates—steps along the process like individual stairs that must be reached in succession—during N2 activation using a specialized setup for electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy. Think of intermediates like a single frame paused in a film.

In the CdS:MoFe complex, the CdS nanocrystals convert the energy of light into high-energy electrons. But this comes at a cost: The excited high-energy electrons leave behind low-energy vacancies called holes. The electrons are used by nitrogenase to drive the reduction of N2 to ammonia. The holes that are leftover must be filled by electron-donating molecules. This process, called hole scavenging, is a key step in the catalytic process and is necessary to keep delivering electrons to the MoFe protein.

Earlier work demonstrated that hole scavenging plays a crucial role in ammonia production efficiency. In the absence of hole scavenging, the high-energy electrons can recombine with the holes, resulting in a loss of the energy needed to drive N2 reduction. Additionally, if the low-energy holes are allowed to accumulate, they may pull electrons out of the MoFe protein, further slowing catalysis. Electrons are a valuable resource in these catalytic reactions, and each electron lost to the holes results in decreased ammonia yield.

The researchers wanted to understand the role of hole scavengers in the efficiency of the light-driven process, so they performed an EPR study of the CdS:MoFe protein at a temperature cold enough to freeze the sample and slow the reaction but not so cold as to prevent electron transfer. They used this approach to experimentally track the presence of specific reaction intermediates of the MoFe protein as a function of time. This, in turn, was used to develop a kinetic model of the ammonia reaction driven by the CdS:MoFe pairing and to test the effects of hole scavenging on catalysis.

“We found that the electron delivery rate was largely determined by hole scavenging—a role played by sodium dithionite, or NaDT. In this experiment, we found that we could increase the NaDT concentration to promote N2 activation,” said Peter Dahl, an NLR postdoctoral researcher in biochemistry. “Knowledge of the role of hole scavenging in this reaction will allow us to tune electron delivery efficiency by dialing in the optimal scavenger concentration.”

Performing reactions in the frozen state also slows things down enough to chart the paths of catalytic intermediates. In the frozen state, NaDT shows a similar effect on kinetics as at room temperature. Researchers were aware of the potential effects freezing might have on the reaction process, but consistent NaDT measurements provide evidence that freezing did not affect NaDT levels.

“The more we can demystify the mechanisms underlying the nitrogenase MoFe protein reaction, the better we’ll be able to control the reaction for more efficient ammonia production,” said NLR group manager and researcher Paul King. “More efficient ammonia production through nitrogenase enzymes can provide new insights into approaches for lowering the energy cost of ammonia production. This can be achieved through innovative technologies that use nitrogen from air and localize production adjacent to agricultural sites that minimize transportation costs.”

Discover other NLR science of biological energy conversion research, including on pathways of electron transfer. Also, learn more about basic energy sciences at NLR and about the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science Basic Energy Sciences program. Read “Pre-Steady-State Kinetics of Nanocrystal: Molybdenum Nitrogenase Biohybrids Reveals Hole-Scavenging Efficiency Is Critical to N2 Reduction” in Cell Reports Physical Science.

Last Updated Jan. 22, 2026